Recently, The Mummy (1999) was re-released in movie theaters for its 25th anniversary. I was so there. Not only was it fantastic to experience that movie on the big screen again - the way it was meant to be seen and heard - but also because The Mummy was the thing that sparked my interest in ancient Egypt, which led to my Egyptology degree, and thus to my current insolvency. Thanks for the student debt, Brendan Fraser.

But seriously, my main question taken away from this movie back in ‘99 was: “Did the ancient Egyptians really believe in curses?” which took me to the library to find out. The unfolding story of thousands of years of civilization found in those books hooked me on the whole culture. (Short answer to this curse question: officially, yes - but not always. Tomb robbers in the ancient world seemed to realize pretty quickly that, if they weren’t caught by the authorities, nothing bad actually came down on swift wings to rip their hearts out of their chests. And nearly every tomb in the Valley of the Kings was plundered in ancient times, so that should tell us something.)

It’s interesting re-visiting The Mummy at this stage, too, because what catches my attention in it now was not what caught my attention a quarter-of-a-century ago: namely, the spoken language and the hieroglyphic writing. My very first day of Middle Egyptian I in grad school, where I was psyched to learn hieroglyphs, started off with the professor talking to us about the ancient Egyptian spoken in The Mummy. First of all, no Egyptologist truly knows what the language sounded like, so you get a variety of different pronunciations.

But in The Mummy, said the professor, you can tell exactly what school of Egyptology the pronunciation was coming out of: it’s the University of California Los Angeles “dialect.” Indeed, UCLA Egyptology professor Dr. Stuart Tyson Smith was the consultant on the movie, translating the actors’ lines into ancient Egyptian by way of Hollywood. And as such, I can’t understand a damn word of it. Well, that’s not entirely true. In The Mummy, I get sm for “priest,” and I definitely hear the word for “temple,” hwt. On that latter word, though, actress Patricia Valasquez, playing Anack-sun-Amun, pronounces it “howt” whereas I learned it as “hoot.” And since hieroglyphs don’t spell out vowel sounds - which is common among ancient Near Eastern languages - we have to guess and insert our own. So sm is usually “sem,” and so forth.

Fun with phonics!

Ancient Egyptian is a tough language. Hieroglyphs can be a bunch of things. Sometimes, they’re ideograms, which means the image represents the thing. Like the letter “m,” which is a figure of an owl, could literally mean “owl.” This was a lot more common in the early days of the language. Hieroglyphs are also phonetic. The letters represent sounds that form words that make up sentences. They can also be determinatives, which are contextual markers at the end of a word that you don’t pronounce. For example, the pronoun “I” or “me” in Egyptian is written as a reed and is pronounced “ee.” If it means the pronoun, there’s the figure of a person next to the reed. But this word is not only a pronoun; it can also indicate speaking or saying something. In that case, the figure next to the reed is still a person, but they have a hand up to their mouth to indicate speech. The amazing thing about sticking with this ridiculously complicated language (don’t even get me started on the grammar) is because learning its ins and outs is as close as we’ll ever come to “getting” the ancient Egyptians. True of all languages for all cultures.

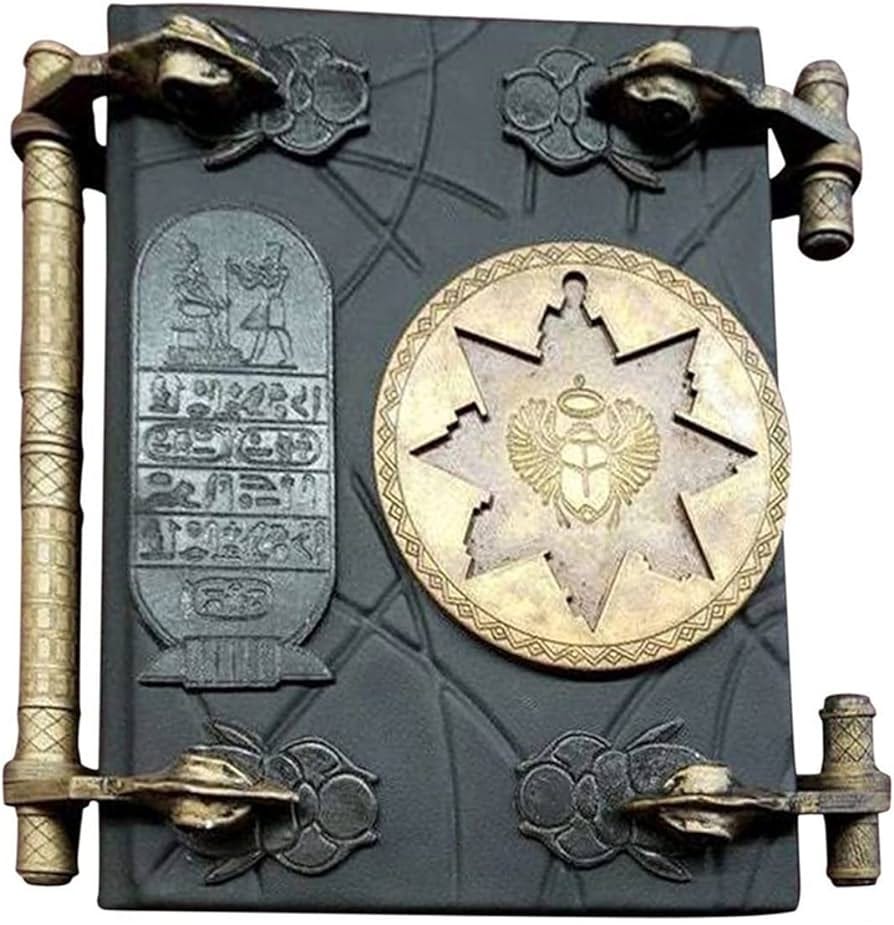

In The Mummy, the most extended performance of spoken ancient Egyptian occurs when curious librarian Evelyn Carnahan (Rachel Weisz) “borrows” The Book of the Dead from the Egyptologist, reads an inscription therein, and brings the mummy Imhotep back to life. Evelyn’s language skills are just too, too good… enough to unleash a curse on the world, to correct someone else’s translation (“It’s ‘for all eternity,’ idiot!”) and gloat over her fast work translating glyphs as a mob is bearing down on her (“Take that, Bembridge scholars!”) The Book of the Dead that she gets her hands on is portrayed as a black, stone book on hinges, with a lock. In reality, the codex-style book was not invented until around 300 BC. The earlier ancient Egyptians wrote portable things on papyrus scrolls, including The Book of the Dead.

The name “Book of the Dead” was invented by the 19th century German Egyptologist Karl Richard Lepsius. The ancient Egyptians referred to it as The Book of Coming Forth by Day (also translated as “Going Forth by Day), which sound a lot less ominous than the scholarly appellation. The Book of the Dead/Book of Coming Forth by Day was a collection of prayers and recitations, designed to help the deceased navigate through the underworld, and individuals either had them commissioned as part of their grave goods, or they purchased them readymade. For the latter, scribes would make generic ones, with blank spaces to fill in the name of the deceased.

If you look at a popularly produced translation of The Book of the Dead, it’s always one particular ancient scroll that is used: it’s the Papyrus of Ani, now located in the British Museum. Ani was a temple accountant and scribe, and his Book of Coming Forth by Day dates from around 1250 BC, the Papyrus of Ani scroll was acquired (I’ve also heard smuggled) from Egypt by the English Egyptologist E.A. Wallis Budge in 1888 AD. It’s a massive scroll, 78 feet in length. Budge set about slicing up the scroll into individual sections, which damaged the scroll’s continuity, then helped publish a facsimile edition and translation.1 Budge’s translation and methods are both really outmoded, derided by Egyptologists everywhere. Still, his is the most common translation out there because it’s in the public domain.

Speaking of derision, many Egyptologists have not wanted to delve into the Papyrus of Ani or any other afterlife writings, and scholarship on them languished for decades. More recent scholars attribute this to snobbish attitudes about “primitive” ancient religions.2 I also wonder about scholars being too intimidated to tackle it. Because to be honest, the Papyrus of Ani and the other books in this genre…they’re weird to us. Almost all religious texts and afterlife material from Egypt is often incomprehensible to scholars, even ones who know the language really well. It’s the concepts that trip them up. The ancient Egyptians wrote these things for themselves, and they didn’t leave behind manuals or everyday catechisms to explain their beliefs. At least, none that have ever been discovered.

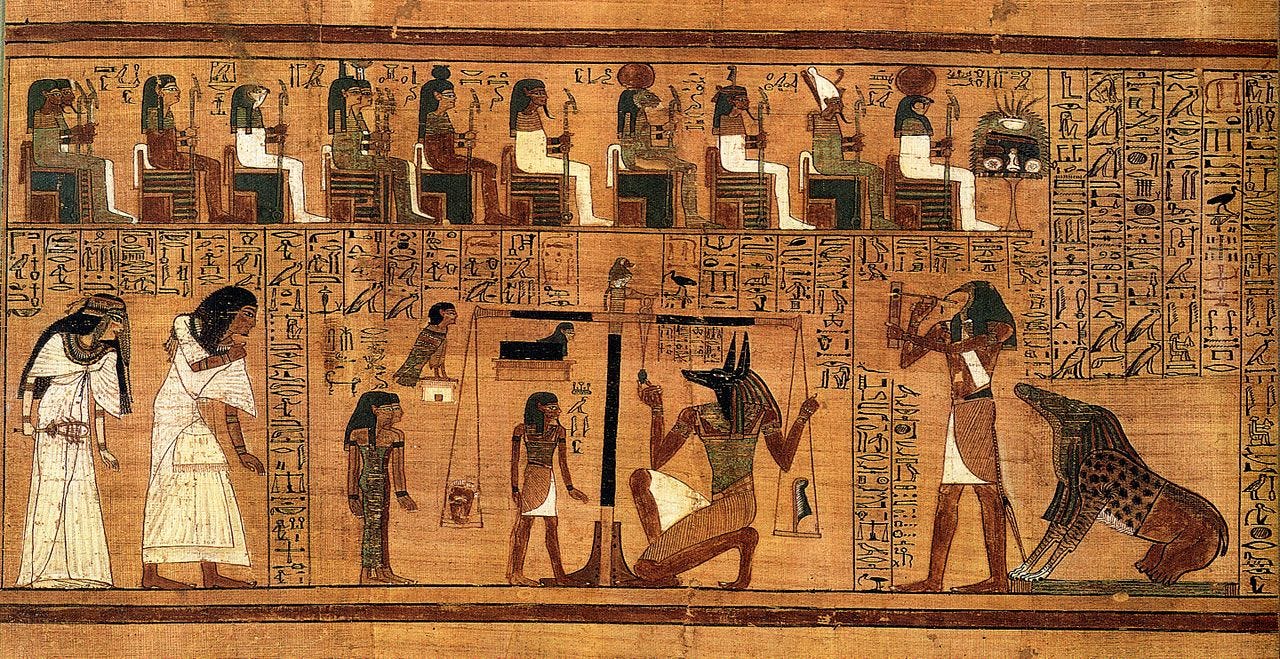

Despite this, the Papyrus of Ani is fascinating - and moving, too, because of its human character. The inscriptions and colorful illustrations depict Ani alongside his wife Tutu as they enter the afterlife together. (Tutu, it appears, was still alive when her husband died, but she’s still there in an aspirational sense.) As for the experience of peering into it:

We enter Ani’s Book of the Dead as we might enter a contemporary tomb, flanked by hymns to the sun god Re, and then by eloquent invocations to Osiris [the god of the underworld]. Passing through these hymns, so to speak, the deceased arrives at the central metaphor of the papyrus and the critical moment of the passage from this world to the next: the weighing of the heart. Here the visual image symbolically represents the judgment of a person’s moral worth as the balancing of his heart against the feather of Maat, the goddess who personified truth, justice, and order.3

The above description comes from a more recent and highly accessible full-color facsimile of Ani’s scroll, with a great translation and extensive, helpful commentary: The Egyptian Book of the Dead: The Book of Going Forth by Day: The Complete Papyrus of Ani by a slew of scholars and artists. Among these scholars is philologist Raymond O. Faulkner, whose translation is the heart of the book. He was quite a guy. In the days before computer programs that could generate hieroglyphs, he handwrote a basic ancient Egyptian dictionary, which I encountered day one of grad school. Getting used to his handwriting on top of learning the language…let’s just say there was a lot of cursing, and it wasn’t coming from the ancient Egyptians. His translation and this overall version of The Book of the Dead is a major accomplishment, and fantastic for journeying through the rich, strange, allusive world of ancient Egyptian thought and belief.

I also have a love for Normandi Ellis’ poetic, self-described “meditation,”4 Awakening Osiris: The Egyptian Book of the Dead. It’s gorgeous and thought-provoking. Here is a bit of how she translates and envisions chapter 15 in Ani’s papyrus, an adoration of the sun god Re:

Where gods have gathered, the heart grows still. A procession of jabiru walk, laying eggs of other lives, of blue souls in another time. Incense rises where gods gather. Heaven and earth are long dreams weighed in the balance. A man is known by his words and deeds. Beautiful is the new sun sailing in a river of sky in the boat of morning. Beautiful is man in his moments in time, a thousand beads of thought on a white string.5

What the Book of the Dead ultimately teaches us is that the ancient Egyptians loved life, not death. They loved life so much that they believed that the next world was just a copy and continuation of the life they already knew…but perfected, for all eternity.

See James Wasserman, “Thoughts on This Twentieth Anniversary Edition” in Dr. Ogden Goelet, et.al., The Egyptian Book of the Dead: The Book of Going Forth by Day: The Complete Papyrus of Ani. Revised Edition. (San Francisco: Chronicle Books, 2015), 11.

J. Daniel Gunther, “Attitudes of the Past” in Dr. Ogden Goelet, et.al., The Egyptian Book of the Dead: The Book of Going Forth by Day: The Complete Papyrus of Ani. Revised Edition. (San Francisco: Chronicle Books, 2015), 14-16.

Dr. Ogden Goelet, “Introduction” in Dr. Ogden Goelet, et.al., The Egyptian Book of the Dead: The Book of Going Forth by Day: The Complete Papyrus of Ani. Revised Edition. (San Francisco: Chronicle Books, 2015), 29.

Normandi Ellis, Awakening Osiris: The Egyptian Book of the Dead (Boston: Phanes Press, 1988), 25.

Ellis, Awakening Osiris, 44.